Some Java interview questions

— java — 1 min read

Currently, I am looking for a new job. Ideally, I'd like to work for something that is really meaningful to me. Anyways, after a one-year break from daily programming business, I thought it's time to get myself prepared again. Of course, I did not stop programming and learning - maybe I learned even more than I would if I were employed. But it is under other circumstances and very broad, I like to try out all kinds of things I read about and found interesting, be it different programming languages, new concepts, techniques, libraries or frameworks.

When you look at job postings though, most companies are looking for specialists. There are also some, that are searching for generalists, but expect them to be specialists for everything. Since I think that this is not a healthy expectation that one can and should live up to, I have thought about what I am most likely to be a specialist in, although I see myself more as a generalist.

I still don't know the answer, but I know that I worked for the most time with Java. That is what companies would also see when they look at my resume. So, I decided to refresh my java knowledge by starting to go through some interview question that circulate on the web. Finally, I made a collection of questions I liked and added some more details to the answers, but also some basic questions, or questions that led me to other questions I liked to have an answer for. I am pretty sure that there are a many more interesting questions and whenever I'll come across them, I'll extend my collection. And these questions I'd like to share with you.

Is Java pass by reference or pass by value?

Java is always pass by value.

It means the argument is copied to the parameter variable, so that the method

operates on the copy. When the value of an object is passed, the reference

to it is passed. If a reference points to a mutable object like an ArrayList

and gets changed inside a method, the originally passed variable is also

affected. Since passing an object as argument also means that the reference to

the object is copied. As a result, both variables(original and parameter) refer

to the same object.

What is unboxing and autoboxing in java?

Autoboxing is the automatic conversion the java compiler makes between the

primitive types and their corresponding object wrapper classes. For example,

converting an int to Integer or a double to Double. If the conversion

goes the other way, its called unboxing.

What is the difference between an abstract class and an interface?

Abstract classes specify what an object is, by defining characteristics of an object type. They can have a constructor and can hold a state.

Interfaces are used to establish a contract about what an object can do. They define capabilities that are promised to be provided by an implementing object.

What are the different access modifiers available in Java?

There are four types of Access modifiers:

public– accessible from everywhere in the applicationprotected– accessible within the package and the subclasses in any package- package private (Default) – accessible strictly within the package

private– accessible only within the same class where it is declared

What is a final class? What is a final method?

A final class cannot be extended.

A final method cannot be overridden.

What is a defender Method?

Defender Methods are default methods, which were added in Java 8 to

interfaces. With them, it is possible to add new methods to interfaces without

breaking existing implementations by defining a default behavior for all of

them.

What is the purpose of garbage collection in Java and when is it used?

The purpose of garbage collection is to identify and discard those objects, that are no longer needed by the application, in order for the resources to be reclaimed and reused.

Describe and compare fail-fast and fail-safe iterators.

fail-fast: Operates directly on the collection itself. Whenever the

collection is modified while iterating it throws a

ConcurrentModificationException. (e.g. ArrayList, HashSet, HashMap)

fail-save: Operates on a cloned copy of the collection. Does not throw an

exception when it gets modified while iterating. (e.g. ConcurrentHashMap,

CopyOnWriteArrayList)

What are Generics in Java ? What are advantages of using Generics?

They were designed to extend Java's type system to allow a type or method to operate on objects of various types while providing compile-time type safety.

What is type erasure?

Generics are checked at compile-time for type-correctness. The generic type

information is removed in a process called type erasure. For example

List<Integer> will be converted to the non-generic type List containing

arbitrary Objects. Because of that, type parameters cannot be determined at

run-time.

What is invariance, covariance and contravariance?

Java’s generic type parameters are invariant. This means for any distinct types

A and B, G<A> is not a subtype or supertype of G<B>. As a real world

example, List<Cat> is not a supertype or subtype of List<Animal>.

To achieve covariance the wildcard operator combined with an extends clause is

used. The type parameter T is covariant in the generic type List<T> when A

is a subtype of B and List<A> is a subtype of List<B>.

To achieve contravariance the wildcard operator combined with an super clause

is used. The type parameter T is contravariant in the generic type List<T>

when A is a subtype of B and List<B> is a subtype of List<A>.

How does the Java memory model work?

The JVM divides memory between thread stacks and the heap.

Each thread has its own thread stack. It contains the call stack, divided into stack frames for each method, that has been called, to reach the current point of execution. These stack frames store all local variables. A thread can only access its own thread stack.

The heap contains all Objects created in your Java application regardless of

what thread created the object, including objects of wrapper classes for

primitive times (e.g. Integer, Double, String).

All local variables of primitive types are fully stored on the thread stack and are not visible to other threads. A local variable may also be a reference to an object, then the reference is stored on the thread stack, but the object itself is stored on the heap. An Object may contain methods that also contain local variables, which are also stored on the thread stack, even if the object the method belongs to is stored on the heap.

An Object's member variables (fields) no matter if primitive type or object reference are stored on the heap along with the object itself. Static class variables are also stored on the heap along with the class definition. Objects on the heap can be accessed by all threads, that have a reference to it.

What are static initializers and when would you use them?

A static initializer gives you the opportunity to run code during the initial

loading of a class and it guarantees, that this code will only run once and will

finish before your class can be accessed in any way.

What is the volatile keyword? How and why would you use it?

The volatile modifier guarantees, that any thread that reads a field, will see

the most recently written value.

These variables are directly written to and read from the main memory instead of the CPU cache. Reading and writing to main memory is more expensive.

If two thread are reading and writing to a shared variable, where the new value

is generated based on the previous value (needs a read before writing), volatile

is not enough. The short time gap between reading and writing creates a race

condition, where multiple threads might read the same value and overwrite each

others value. In that case you need to use synchronized keyword (or

AtomicReference, AtomicInteger, ...) to guarantee atomic reads and writes.

One common use-case for using volatile is for a flag to terminate a thread.

What is the synchronized keyword?

Synchronized blocks can only be executed by a single thread at a time. They can thus be used to avoid race conditions.

Without the synchronized keyword there are no guarantees about when a

variable, that is kept in a CPU register by one thread, is written to or

refreshed by reading from the main memory.

By using the synchronized keyword, all variables visible to the thread are

refreshed before entering the block and all changes to variables will be

committed back to the main memory when leaving the block.

For more advanced locking semantics Read/Write Locks are used. There are Lock

interface implementations, which can be used for reading and/or writing with an

optional fairness policy for the acquisition order enabled.

What is the ThreadLocal class? How and why would you use it?

A ThreadLocal instance is used to individually manage a state/value per

thread. Whenever it is used inside a thread, it accesses its own independently

initialized copy of the variable. Each thread holds an implicit reference of a

ThreadLocal variable as long as the thread is alive. It provides a simple way

to make code thread safe.

What is a deadlock?

A condition that occurs when two processes waiting for the other to complete, before they proceed. As a result, both processes wait endlessly.

What is singleton class and how can you make a class singleton?

An implementation of the singleton pattern must:

- ensure that only one instance of the singleton class ever exists

- provide global access to that instance

Typically, this is done by:

- declaring all constructors of the class to be private

- providing a static method that returns a reference to the instance

The Bill Pugh singleton implementation from above, is the most widely used

implementation to provide a thread safe singleton. It uses an static inner class

for holding an instance of the enclosing class. This SingletonHolder class is

not loaded until the getInstance() method is called. Before the calling thread

is given access to it, the static instance is created as part of class loading.

This means safe lazy loading without any need for synchronization/locks.

What is the Java Producer-Consumer Problem and how can you solve it?

The consumer-producer problem, also knows as the bounded-buffer problem, is a classic example of a multi-process synchronization problem. It describes two processes, the producer and the consumer, which share a common, fixed-size buffer used as a queue. The producers job is to generate data, put it into the buffer and start again. At the same time, the consumer is consuming the data and removing it from the buffer, one piece at a time. The problem is to make sure, that the producer won't try to add data to a full buffer and that the consumer won't try to remove data from an empty buffer.

It can be solved by synchronized access to a Queue implementation like

LinkedList and the use of wait() and notify() for inter-process

communication.

Another easier approach could be to use a BlockingQueue, that is already

handling synchronization and communication internally.

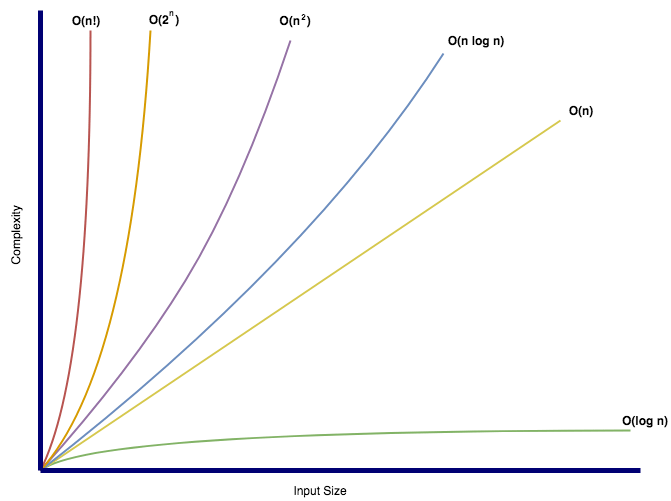

What do you know about the Big O notation?

The Big O notation, also called Bachmann-Landau notation, is a relative representation of the complexity of an algorithm.

It is used for comparing algorithms according to how their run time or space requirements grow as the input size grows. Big O always assumes the worst-case. Regardless of the hardware, O(1) is always going to complete faster than O(n!).

List

| Data structure | Access | Prepend | Insert | Append | Delete | Search | Traverse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ArrayList | O(1) | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) / O(n)* | O(n) | O(n) | O(n) |

LinkedList | O(n/2) | O(1) | O(n) | O(1) | O(n) | O(n) | O(n) |

CopyOnWriteArrayList | O(1) | O(2n) | O(2n) | O(n) | O(2n) | O(n) | O(n) |

Queue

| Data structure | Peek | Offer | Poll | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

LinkedList | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

PriorityQueue | O(1) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(1) |

ArrayDeque | O(1) | O(1) / O(n)* | O(1) | O(1) |

ConcurrentLinkedQueue | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) |

ArrayBlockingQueue | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

Map

| Data structure | Access | Insert | Delete | Next | Search |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HashMap | O(1) | O(1) / O(n)* | O(1) | O(c/n)** | O(c+n)** |

LinkedHashMap | O(1) | O(1) / O(n)* | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) |

TreeMap | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n) |

** c is the table capacity

Set

| Data structure | Insert | Delete | Next | Search | Traverse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HashSet | O(1) / O(n)* | O(1) | O(c/n)** | O(c+n)** | O(c+n)** |

LinkedHashSet | O(1) / O(n)* | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) | O(n) |

TreeSet | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(n) |

** c is the table capacity

Where would you use LinkedList and where an ArrayList?

ArrayList is to be preferred, when you have a lot of random access via

List.get(n). Even more, when elements are appended instead of being inserted

at a specific index. Both operations have a complexity of O(1)* for

ArrayList.

LinkedList has a higher complexity of O(n) for random access via

List.get(n). But prepending elements has a lower complexity of O(1) for

LinkedList compared to O(n) for ArrayList. Same applies to the removal of

the first or last element in the list. Also, insertions and removals of elements

at a specific index are on average faster for LinkedList.

Therefore a LinkedList is preferable when you rather have prepends, head/tail

removals or removals and insertions at a specific index, while you do not have a

lot of random access.

What is the Java class loader? List and explain the purpose of the three types of class loaders.

The Java ClassLoader is part of the JRE and is used to load classes at runtime

on demand (lazy-loading) into the JVM. These classes can be loaded from a local

or remote file system or even from the web. When the JVM is started 3 kinds

of ClassLoader are used.

Bootstrap class loader - The JVM built-in class loader, which defines the classes in a handful of critical modules, such as

java.base.Platform class loader - All classes in the Java SE Platform are guaranteed to be visible through the platform class loader. In addition, the classes in modules that are standardized under the Java Community Process but not part of the Java SE Platform are guaranteed to be visible through the platform class loader. (e.g.

java.net.http)System class loader, also known as application class loader, that defines classes on the application class path and module path. It is the default loader for classes in modules that are neither Java SE nor JDK modules. The platform class loader is a parent or ancestor of it, so it can load platform classes by delegating to its parent.

Which language features have been added since Java 8? Can you name some?

How to clone an object in Java?

To clone an object in java it is necessary to implement the Cloneable marker

interface and to override the Object.clone() method to make the protected

clone method accessible. Inside the method the value of super.clone() is

returned. By default java is doing a shallow copy of the object. That means all

fields of a primitive type are getting copied, but for objects only the

reference is copied. When a deep copy is created, all values of the object are

copied to a newly created object, regardless of how deeply nested they are.

Shallow copy:

Deep copy:

What is the JIT Compiler?

The Just-In-Time Compiler is a component of the JVM runtime environment, that improves the performance of java application by optimizing code and compiling bytecodes to native machine code at run time.

What is the native keyword in Java? When is it used?

The native keyword in java is applied to a method to indicate, that a method

is implemented in platform native code using JNI (Java Native Interface) / JNA

(Java Native Access). They are implemented in other languages, not in java. For

example, if you need to call a library from Java that is written in another

language or if you need to access system or hardware resources that are only

accessible from other languages (typically C).

References

- https://www.toptal.com/java/interview-questions

- https://howtodoinjava.com/interview-questions/core-java-interview-questions-series-part-3/

- https://medium.com/@yuhuan/covariance-and-contravariance-in-java-6d9bfb7f6b8e

- http://tutorials.jenkov.com/java-concurrency/java-memory-model.html

- http://tutorials.jenkov.com/java-concurrency/volatile.html

- http://tutorials.jenkov.com/java-concurrency/synchronized.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Singleton_pattern

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_O_notation

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/479142/when-to-use-an-interface-instead-of-an-abstract-class-and-vice-versa